Beyond Fluency: Challenging Ableism Through Deaf and Stammered Communication

The conversation about disability is often reductive and condensed into singular narratives. This blog will discuss the intersectional perspectives shared in ‘Christine Sun Kim in Friends and Strangers’ and the work of Dysfluent magazine, an independent publication exploring “lived experience of stammering facilitating contrasting and challenging views” (Foran, 2019). These perspectives echo Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality, which highlights how systems of oppression—such as ableism, racism, and sexism—interact to create unique experiences of marginalisation that cannot be understood through a single-axis lens (Crenshaw, 1990).

Christine Sun Kim’s reflection on deafness in Friends and Strangers is beautiful and confronting, centring round the echoes and repetitions that exist in her lived experience as a Deaf Asian-American artist in her work and communication style (2023). What is striking about Kim’s work is that she reflects the systemic pressure asserting on Deaf (and by extension, other disabled) people; a constant refrain asking why she isn’t adapting to an ableist and hearing world.

Kim points to how her Deafness is not a ‘lack’ of hearing, but a rich cultural identity expressed through ASL. Her way of communicating is marginalised in favour of linguistic ableism which is compounded by cultural and racial bias through assumptions made on her appearance as an Asian woman. Kim shares moments where people speak to her interpreter instead of her; an act not just rooted in ableism, but also through entrenched cultural assumptions where Asian women are seen as passive or infantilised. Kim’s experience demonstrates intersectionality in action: her Deaf identity is not experienced in isolation, but interwoven with racialised and gendered expectations that shape how others perceive and interact with her. As Crenshaw argues, it is at these intersections where social injustice often goes unacknowledged (Crenshaw, 1990).

Kim’s use of performance and visual work pushes back on dominant norms of communication and expression and acts as a way of self-defining her identity whilst criticising the systematic marginalisation of disabled people and their nuanced identities.

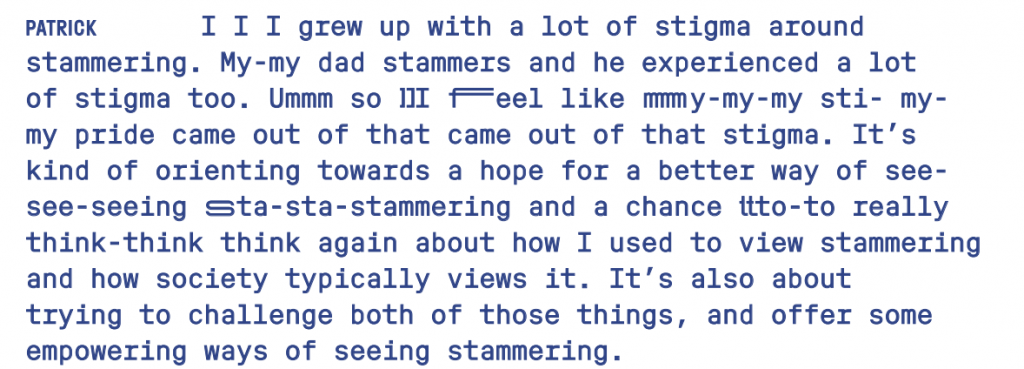

Dysfluent magazine speaks to this consideration of language, disability and representation. Focused around the experience of stammering, the magazine interviews various participants about the challenges and preconceptions about navigating a hyper-fluent world, as well as the joy, pride and space that can arise from stammers. This is reflected in the bespoke typeface used in the publication; a stammer in the interview is visually represented and presented as an integral part of the conversation and communication (Angelos, 2021). A large emphasis behind this project is the aim to move the concept of stammering from a sense of a problem to be “fixed” and into a mode of understanding where it is seen as “a natural variation.. in a social justice effort that celebrates human diversity” (Foran, 2023, p. 3.).

Stammering has intersectional implications that are explored by Dysfluent; for example, people of colour, immigrants or multilingual speakers who stammer may experience compounded prejudice with racial bias mixed with assumptions about intelligence or education based on speech, as well as assumptions about language background (Singhal, 2023, p. 91). In addition, there are socio-economic considerations linked to stammering as fluency may be unfairly linked to employability or competence.

In terms of considering these lived experiences and disability considerations within my own teaching context, it has reinforced proactivity rather than reactionary. Inclusionary teaching practice needs to be present at the point of planning. Using Deafness and stammering as examples, here are some of the actions that could be taken:

- Facilitate student control over their participation, such as choosing when or if to speak in group settings;

- Offer non-verbal participation options if preferred, such as written answers, sketches, visual presentations;

- Avoid putting people on the spot to speak without warning;

- Offer alternative formats for presentations such as extra preparation time or recorded video or audio submissions instead of a live delivery.

Dysfluent and Christine Sun Kim emphasize how the intersection of identities can either deepen marginalisation or, with proper support and empowerment, create strong communities of resistance and creativity. They urge us to hold space for complexity, embrace a person-centred approach where institutions must proactively adapt, and to challenge the narrow ways in which we often talk about and perceive disability. By applying Crenshaw’s intersectional lens, we are better equipped to move beyond surface-level inclusion and work toward genuinely transformative practices that recognise the full complexity of disabled identities (Crenshaw, 1990).

Image references

Figure 1. Christine Sun Kim (2019) Why most of my hearing friends do not sign. [Screenshot from Instagram] Available: https://www.instagram.com/p/B3JeYUxoR8m/?hl=en&img_index=1

Figure 2. Christine Sun Kim (2019) Museum visits are hard on my body. Rest here if you agree. [Screenshot from Instagram] Available: https://www.instagram.com/p/B557DlCIQeQ/?hl=en&img_index=1

Figure 3. Conor Foran (2023) Screenshot of Dysfluent magazine and Dysfluent Mono typeface. [Screenshot of digital version of Dysfluent: stammering pride. Issue 2].

References

Angelos, A. (2021) ‘Stretched and repeated, Dysfluent Mono is a typeface that embodies what it means to have a stammer’ in It’s Nice That. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/dysfluent-magazine-dysfluent-mono-typeface-graphic-design-130121

‘Christine Sun Kim in “Friends & Strangers”’ (2023) Art in the Twenty-First Century, Season 11. 20th October. Available at: https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s11/christine-sun-kim-in-friends-strangers/ [Last accessed: 10th May 2025]

Crenshaw, K. (1990) Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43 (6), pp.1241-1299

Foran, C. (ed). (2019) Dysfluent. Available at: https://dysfluent.org/magazine [Last accessed: 10th May 2025)

Foran, C. (ed). (2023) ‘Editor’s Note’ in Dysfluent: stammering pride. Issue 2, pp. 3 – 5.

Singhal, P. ‘Advocating for unity: a conversation about diversity, activism and social media’ in Dysfluent: stammering pride. Issue 2, pp. 89 – 96.

Leave a Reply