Neutrality as Exclusion

I have found the topic of faith and religion the most challenging to approach so far in the Inclusive Practices unit and it has been interesting to analyse why that might be the case. When speaking about disability or race, I feel more equipped with language to discuss as they appear to have more visibility in higher education vernacular (for example, discussions on decolonising the curriculum, increasing diversity and inclusion through representation and accessibility policies are regular and recurring focuses within Library Services). This is not the case with religion or faith which largely is unspoken about.

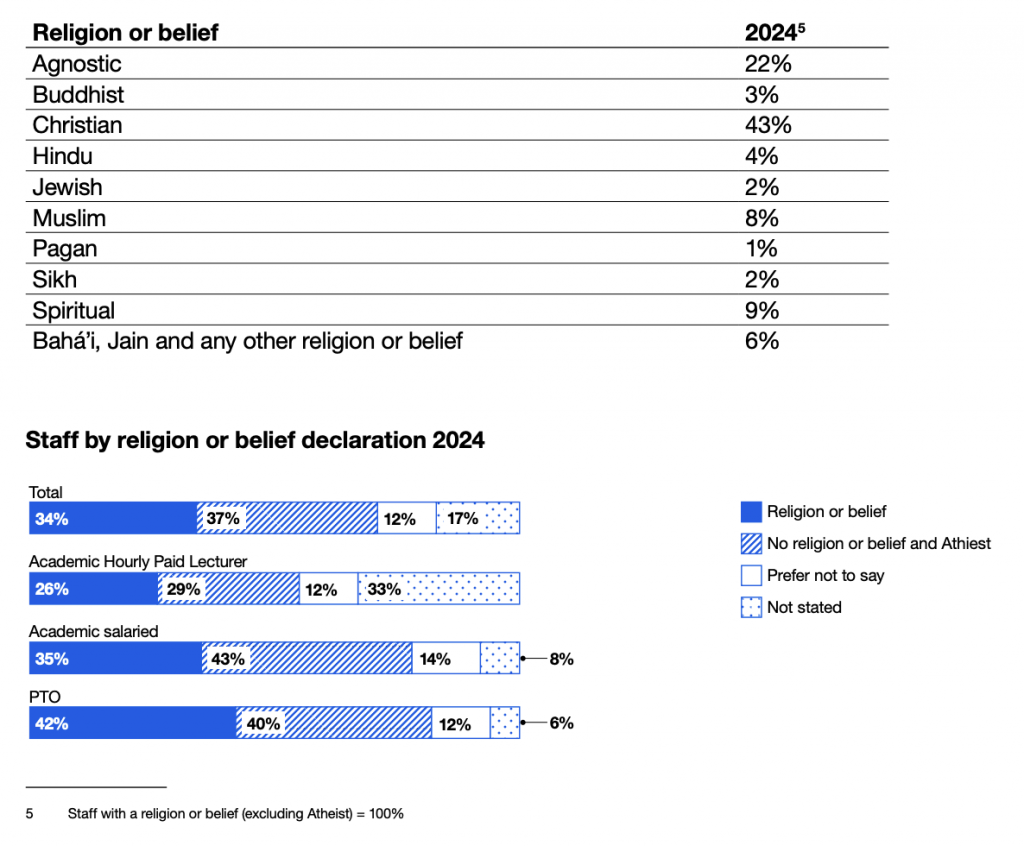

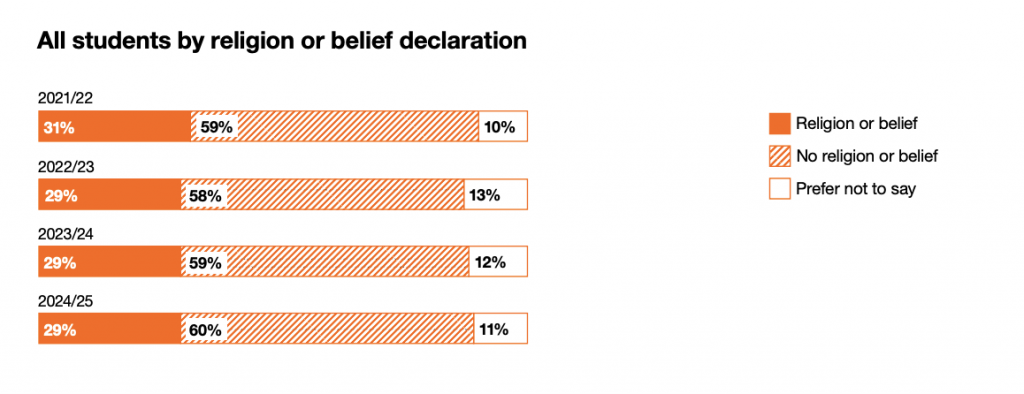

A main factor at play is my assumption or perception of Western higher education as tacitly secular and post-religious which is compounded by my own positionality as a non-religious person. As a result. I do not often consciously think about religion and faith in my teaching practice. However, according to the UAL Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Data Report 2024, 34% of staff and 29% of students have declared a religious belief marking a significant proportion of our pluralist university community (UAL, 2024).

My understanding of higher education as post-religious falsely identifies universities as neutral spaces that can “preserve and protect pluralism, allowing… all equal inclusion in public discourse” (Stolow and Boutros, 2015, p.5.). However, this approach often ends up excluding and othering religious people as this neutrality within the Western higher education setting is contextually coded as secular (Kitching and Gholami, 2023).

Throughout this unit, there has been a recurring theme of institutional practice rendering marginalised groups as simultaneously invisible and visible. Institutional practices of neutrality become “mechanism[s] of erasure” (Ziadah, 2025) whereby religious practices are all but ignored until they are made hyper-visible due to their explicit oppositionalism to this secular ‘neutrality’. A clear example of this is wearing the hijab as a hyper-visible religious identifier and opens up a “‘triple penalty’ where religion, gender and colour intertwine” (Ramadan, 2022, p. 35). Ramadan illustrates that institutional norms often prioritise secularism and implicitly expect religious neutrality; the Muslim women academics interviewed in the article are exposed to persistent and Islamophobic stereotypes—such as being oppressed, submissive, or lacking agency. It exposes the underlying toxicity of adopting a secular lens which often frames religions as being incompatible with intellectual authority. I found it striking that in Ramadan’s article, the academics interviewed were the ones advocating for inclusive policies and dismantling Eurocentric curricula. It made me think of Sara Ahmed’s warning of the burden of diversity and inclusion often falls on minority staff becoming responsible for this work, whilst also “inhabiting institutional spaces [where they are] less valued” (Ahmed, 2012, p.4).

I am conscious that I have not offered any solutions or strategies to implement into my teaching practice, but challenging and critically unpicking my understanding of my own positionality and institutional structures impacting religious freedom is a key first step. Neutrality is a false concept that does not serve plurality and sets a dangerous precedent and excuse for upholding exclusive and dismissive approaches to religious expression.

Image references

Figure 1. UAL (2024) UAL Staff by religion or belief declaration 2024 [Screenshot from document]. Available from https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/472836/UAL-EDI-data-report-2024-PDFA.pdf

Figure 2. UAL (2024) UAL students by religion or belief declaration [Screenshot from document]. Available from https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/472836/UAL-EDI-data-report-2024-PDFA.pdf

References

Ahmed, S. (2012) On being included: Racism and diversity in Institutional Life. London: Duke University Press.

Kitching, K. and Gholami, R. (2023) ‘Towards Critical Secular Studies in Education: addressing secular education formations and their intersecting inequalities’ in Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 44(6), pp. 943–958. Available at: doi: 10.1080/01596306.2023.2209710. [Accessed: 29th May 2025]

Ramadan, I. (2022) ‘When faith intersects with gender: the challenges

and successes in the experiences of Muslim women academics’ in Gender and Education, 34(1,) pp. 33-48. Available from DOI: 10.1080/09540253.2021.1893664. [Accessed: 29th May 2025]

Stolow, J. and Boutros, A. (2015) ‘Visible/Invisible: Religion, Media, and the Public Sphere’ in Canadian Journal of Communication, 40(1), pp. 3–10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2015v40n1a2977. [Accessed: 29th May 2025]

UAL (2024) Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: Data report 2024. Available at: https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/472836/UAL-EDI-data-report-2024-PDFA.pdf [Accessed: 29th May 2025]

Ziadah, R. (2025) ‘Genocide, neutrality and the university sector’ in The Sociological Review, 73(2), pp. 241-248. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261251321336 [Accessed: 29th May 2025]

Leave a Reply